<Back to contents> <Next chapter>

2 - ARRIVAL

It was in my second year on Skiathos that I bought the piece of land in Zorbathes Valley that has become my home, although, at the time, I didn't’t realise just how strong an attachment I would have to it and Skiathos. I bought it with two American friends who were subsequently busted for possession of marijuana and never enjoyed Zorbathes and the hopes and dreams that they had had for living here. I had met them the first day I arrived on Skiathos and shared a meal in the tiny kalivi that they then inhabited in the back of the Kolios Valley. However, I had already had their names on a piece of paper that was given to me by a German girl in Freiburg who was the first person to ever mention the name “Skiathos” to me. In retrospect, fate (or the Greek Gods) was making sure that I came to Skiathos.

It began like this.

I left Britain in the autumn of 1971 with enough money (inherited from a Great

Aunt) to achieve an old ambition of mine, which was to travel around the world.

I left behind me a cloud of hash smoke, a haze of LSD and a lot of friends and

acquaintances with whom I had been sharing the hippie life for several years.

I inevitably went straight to Amsterdam, which was, and still is, my favourite

city, and purchased an old, beat up, Volkswagen van to travel in. As often happened

in Amsterdam, I stayed longer than I had intended to and I didn't leave until

late February 1972 after experiencing one of the coldest winters I can remember.

I had been living in a “Kraakhuis” (Dutch for “Squat”

which is English for an abandoned house that was used by hippies and others

to live in). We had only boards over the windows and the wind blew a freezing

chill in through the cracks.

Living with me was Annette, a Dutch girl who I thought I was in love with. She

almost certainly liked me a lot but was not as “romantic” as I was

about our relationship. It went awry, as these things tend to do when the flow

of love (or what is thought to be love) is mostly one sided, and we split up

fairly amicably.

I left the house with some relief and stayed with my old friends Chris and Rose

in the Jordaan area before setting out to get some sunshine. Not really knowing

where I was going, I headed for Freiburg to see Mike, a German guy I had met

the year before via George, an American friend who had stayed with me for some

time in Hounslow, England. In the course of my stay here Mike took me to a party

where a German girl called Gabi asked me what I was doing and where I was going.

Actually I didn't know the answer to either of these questions as I was in the

situation of being a free man with a reasonable amount on money, no emotional

ties to anything or anyone and the only real thing on my mind was to find somewhere

warm to soak the cold of the Kraakhuis (and my failed love affair) out of my

bones. Anyway, I told her most of this and said that maybe I would go to Spain

(but I had already been there a couple of years before), maybe Corsica (it sounded

fairly exotic), but probably Greece, as I fancied going on to India and then

down to Australia and eventually around the world. She said that if I was going

to go to Greece, I should go to Skiathos as it was a beautiful island and there

were some good people living there. She might well have said Timbuktu and I

would probably have said yes, but Skiathos it was. She wrote down a list of

names of people living there. All of these people became very important in my

life and all that happened to me afterwards on the island, but I did not know

that at the time.

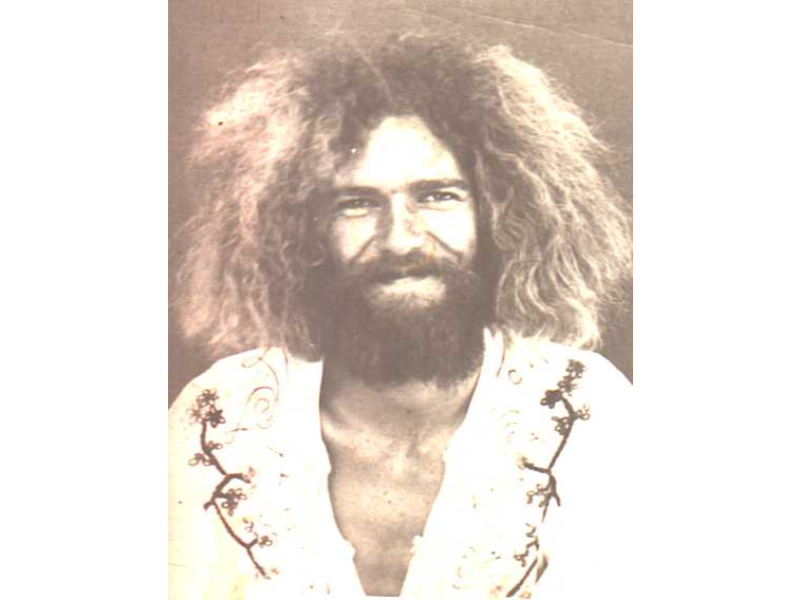

Perhaps I should digress here a little bit and describe myself. I was 23 and

had been a traveler and hippie for the previous 3 years. I had (used to have!)

lots of curly hair; a beard and a moustache and you couldn't’t see much

of my face except my eyes! This is the little signature doodle I used to add

to my letters:

and here’s a photograph:

I left Freiburg a couple of days later and had an eventful trip down through

Austria and Yugoslavia (then a backward but reasonably safe place). I picked

up hitchhikers all the way down to pass the time and repay my debts from my

old hitchhiking days. On 6th March 1972, I arrived at the Greek border and drove

down to Volos.

The following day I took a ferry to Skiathos. Upon arrival, my old camper van

must have sensed more than I did about the island as its battery had gone flat

on the ferry and it (and I) had to be pushed down the unloading ramp. The van

must have known that one day it would die here (which it did), I wonder if it

knew more, and saw my fate too? I found Yanni, who was a taxi driver and whose

name I had from Gabi, and he recharged my battery. Whilst waiting for my battery

to charge, I had noted a group of longhaired foreigners sitting at a kafenion,

who subsequently drove off in an old VW coupe.

That afternoon I was sitting in the bank waiting to change some travelers cheques

(it took seemingly massive amounts of paperwork and many signatures including

the bank manager’s) when Keith, one of the longhairs, came in and asked

the manager if he had left his car keys there as he had mislaid them. No one

had seen them, but I said that if he had no luck finding them, I would be quite

happy to give him a lift wherever he needed to go to. He said he would be back

soon and shortly returned to take me up on my offer. I drove him halfway along

the island and parked on the main road at Kolios and he then asked where I was

staying (I had not the faintest idea) and would I like to share a meal with

him and his lady as thanks for giving him the lift. Of course I accepted and

we trudged through a boggy field to his kalivi. A kalivi is usually a one room

stone cottage, often built half off the ground so that the mule or donkey and

goats could be stabled underneath, with a small hearth in the corner for cooking

and warmth. Here I met Paula, his lady, who was cooking a stew over a wood fire

in the corner fireplace of a room not much bigger than some people’s walk-in

closets.

This is how I met the couple with whom I bought Zorbathes and who were among

those on Gabi’s list.

Keith & Paula in their kalivi.

I showed them the list and they remembered Gabi as the girl that had stayed

with Jim, an Englishman, the summer before. They also gave me a quick run down

on the other people mentioned on her list; Reese and Patty, an American couple,

and Franz (a South African giant who Keith was helping to build some tourist

accommodation at Vasilias). We had a wonderful, if simple, meal and I found

myself liking immensely the couple and the romantic life style they lived, which

was completely removed from anything I had ever experienced. Afterwards we talked

about traveling and Keith told of his adventures in India, where he had lost

so much weight from dysentery, that when Paula had met him at Athens airport,

she had not recognised him. Keith suggested that I should drive the van to the

beach of Vasilias (there was a narrow dirt track down from the main road) as

I could park and camp next to the sea and it was reasonably near the only town,

Skiathos. I left them quite late that night having sampled retsina and ouzo

and staggered back in pitch darkness to my van. Until that night, I had never

been in total darkness (there had always been street lights or something to

light my way) and I had to cure myself of my childhood fear of the dark or stay

out all night. Someone had once told me that there was nothing “out there”

in the dark that hadn't been there in daylight so what was there to fear. I

repeated this to myself as I made my way to the van and realised, as I got there,

that in fact, it was true, and the fear was in me and not outside. The first

lesson that Skiathos taught me.

I drove the next morning to Vasilias Beach and, once we were down the dirt track,

the van immediately refused to start again and I found that I was going to be

there for a while, or at least until I could fix the starter motor. Being an

engineering idiot at the time (and I am not much better now) it looked like

I would have to get someone out there to fix it. The place was beautiful, being

just 10 metres from the sea andI was parked under the shade of a pretty old,

if not ancient, olive tree. The sun was still not very strong, it was March

after all, but it seemed like balm to me and I spent some time just sitting

around soaking up the warmth and the light (which is so special in Greece).

It then proceeded to rain for 2 days, which was pretty miserable, but then the

sun returned, and it became glorious. Everything smelt so fresh and the first

spring flowers started to push their way through the earth. I was fascinated

by the old olive tree whose trunk was so gnarled and twisted that I found myself

studying it for hours at a time. Little did I realise that my soul was being

captured by the magic of Greece and this particular island.

It turned out that the apartments Franz was building, with Keith’s help,

were just a short walk up a steep track above Vasilias Beach and I would often

nip up for a cup of tea and a game of cards in Keith’s lunch break.

Franz making sandals

Franz was in Athens buying furniture and Pam, his then English lady friend,

asked me after a couple of days whether I wouldn't rather stay up in one of

the apartments and help with some of the work and keep an eye on them when she

and Franz were away. Pam surprised me by telling me she thought I was the most

“together” person around, with my ready smile and friendliness to

nearly all I met. I was still a pretty shy guy at that point and didn't have

much self respect or self confidence. Pam’s comment started me on the

road to discovering who I was and accepting myself as such.

I must explain here that I had never intended to stay more than a couple of

weeks on Skiathos and I wanted to continue on my travels onwards soon. However,

offers like Pam’s kept popping up and I didn't’t leave until much

later that year.

I accepted the offer, but was a bit nervous about meeting Franz who everyone

said was a massive South African Boer who would knock your head off as soon

as look at you. The Greek workers who were still finishing the basic structure

of the second apartment were definitely in awe of him. He finally returned from

Athens and was indeed a giant. Well over 6 foot (around 2 metres+) with feet

the size of dinner plates. However, he turned out to be a rough diamond with

a good heart and only put on his (seemingly) fierce side when the Greeks wouldn’t

come to work because it was raining (or some such excuse).

Franz at Vasilia Beach with Lida in the background.

The house cat was a young male called Kippen by Keith who had a wonderfully

dyslexic way of naming things or people that seemed to hit the nail on the head.

Kippen was not the brightest of cats and proved this one day by not noticing

that we had replaced a pane of glass in the door that he used to come in and

out of, cat door fashion. He just jumped up without checking and banged his

head against the new glass. After thinking about it for a bit, he must have

come to the conclusion that he had got the wrong side of the door and promptly

jumped up and hit his head against the pane of glass next to the first one.

We were rolling on the floor with laughter and it took us quite a time to get

back to some serious work. Kippen, meanwhile, gave up and stomped off in a huff.

(The following winter, Kippen came to stay with me in a kalivi and once crept

so close to the fire embers to sleep that he managed to singe himself and leapt

out of the kalivi window yowling with pain!)

Keith came down and looked at the car and with a few taps of a hammer and a

turn or two with a spanner, freed the starter motor. To celebrate, we drove

to the far end of the island to Aghia Eleni Beach where I promptly drove the

car off the end of the road and into the sand. It took us several hours, a lot

of brushwood and a huge amount of serious swearing to get it out again and I

began to wonder if Keith thought I was as big a dick head as I was feeling.

He never told me and I never asked!

Keith introduced me to Jim who was villa sitting and had access to hot water,

a shower, and a bath, and was frequently visited by kalivi dwellers in need

of a monthly scrub. I also met Reese and Patty, the American couple who lived

in a tiny kalivi further back in the woods from Keith’s. Patty greeted

me with the rather disparaging comment of being “the boy with the list”,

but they turned out to be a friendly and interesting couple who acted as the

mainstay of the kalivi crowd. Patty had money and they had bought their kalivi

and the land around it. However, they lived a very simple vegetarian life, spoke

a fair amount of Greek and looked as if they had been there forever. I was a

bit overawed by Reese who, with his long hair and beard, wise eyes and slow

American drawl, seemed like some kind of guru.

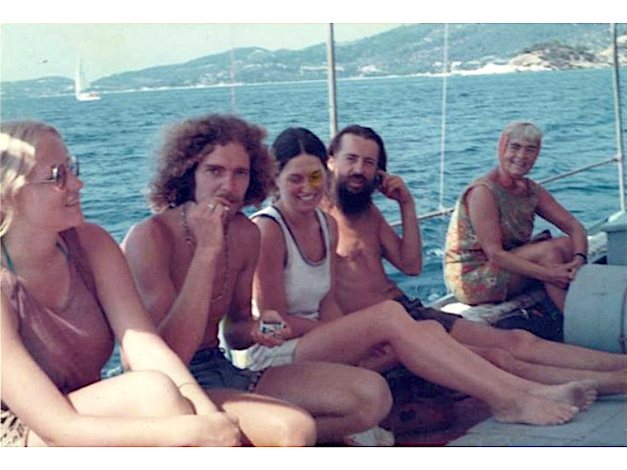

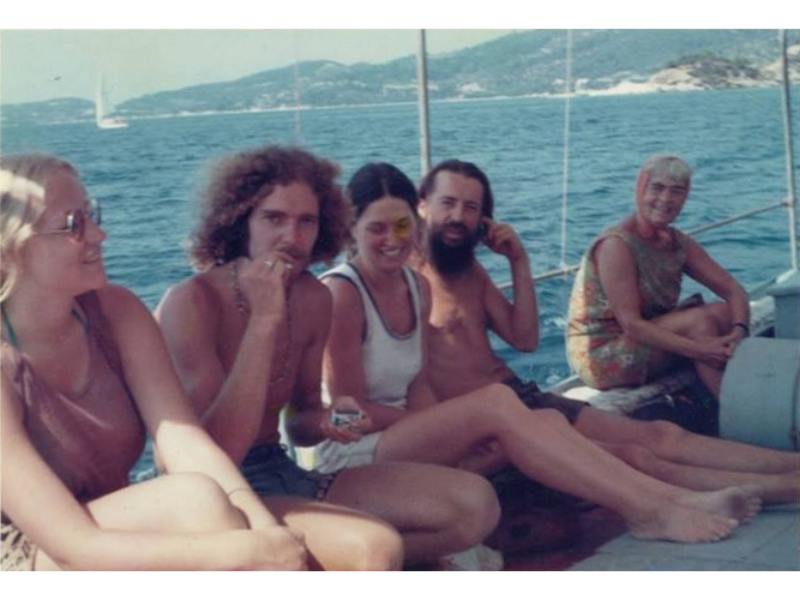

Annette, Geof, Patti, Reese, & Reese's mother, Bess

Keith, Paula and I celebrated my 24th birthday in Skiathos Town where they

showed me a couple of the local tavernas both of which still exist today; Stamati’s

and Messogio. We ate and drank copiously (in fact I got pretty drunk which does

not happen to me often). The food was great and the wine was wonderful and it

cost all of 30 Drachmas per head. At this time a US dollar was worth just about

that amount and I just couldn’t believe how cheap the night had been.

Keith and I also spent several afternoons at an ouzeri (where the Oasis bar

and café now is) under the shade of a massive plane tree, watching the

comings and goings, drinking karafakis of tsiporo and snacking on the mezedes

that came with them. A karafaki was about 4 small shots of tsiporo (like ouzo

but purer, in theory,) and each one came with a substantial plate of little

fried fish, calamares, fried courgette or aubergine slices, or dips of skorthalia,

tsatsiki, or taramasalata. Each karafaki with its plate of mezedes cost just

17 Drachmas so with 51 Drachmas, we were feeling very merry and full of goodies

to boot.

We had formed a pretty close friendship by then although I was still the “new

boy” on the island and someone often viewed with not a little suspicion

as “the one with the list”. You have to remember that this was still

the time of the Colonel’s Junta dictatorship and many people were afraid

of just disappearing. The CIA was reckoned to be mixed up in all kinds of skulduggery

and this (apparently innocuous) person (me) with a list of names was perhaps

not all he might seem.

I eventually met everyone whose name Gabi had given me and they all became close

friends and/or people who influenced me in many positive ways. Looking back

on that evening in Freiburg, I realise now that fate had intended me for Skiathos

although I was completely oblivious to it at the time.

Reese and Patti had two horses called “The Bay” and “The Brown”,

after their colouring, and were busy planning and building a stable for the

animals. The stable was about three times the size of their own living quarters

in the kalivi but the horses were also about three times as big! Patti had money

from her parents and Reese was a hippie from way back and a fascinating man.

With the help of Franz, (who could build the Acropolis in a few days if he put

his mind to it) the stable was built in the course of a few Sunday’s work.

A "work party” would be set up to pour the foundations (for example),

followed by wine and food and a celebration of achieving something solid. This

became a pattern for several building projects (including our own first house)

and is a wonderful way to get a lot done in a day and have fun at the same time.

This was also my first experience with seriously hard work. Mixing concrete

by hand and then humping it up ladders to pour a ring beam was something I had

never encountered before. I loved it and even looked at the (painful) blisters

on my hands with pride.

Still, time had progressed, Franz was ready to let his apartments out and I

thought that, nice as Skiathos was, it really was time to think about moving

on. However, one day, Keith mentioned that an English lady called Betsy who

had a kalivi on the north side of the island and had lots of animals that needed

looking after while she returned to England for a couple of months, was desperately

looking for someone to “kalivi sit” and keep the animals alive whilst

she was away. It was a free roof and perhaps an interesting experience, he told

me. So we went to see Betsy.

Betsy & Paula

She was an eccentric Englishwoman who spent half her time in England and half on the island. With the rent from her house in London, she could live comfortably, if parsimoniously, in Greece, and her excuse for doing so was that she was writing a history of the island. She kept chickens, rabbits, cats, a dog and a donkey. The donkey was necessary as her kalivi was 45 minutes brisk walk from the village or 25 from the nearest road. Keith took me up by a “short-cut”, a path that disappeared into nothing but scrub and I was introduced to the delights of thrashing around in the undergrowth, brushing spider’s webs (and spiders!) off my face. We eventually found Betsy’s, which was a conurbation of one-room kalivis, some joined to each other, others separate, with an incredible view across the sea to the neighbouring island of Skopelos. Betsy showed me around the place and told me of the chores. Apart from looking after the animals (and trying to stop them becoming constantly pregnant), there was a newly planted vineyard that needed watering through its first summer.

Betsy & Thanasis watering the vineyard

The situation was however, magic, and with little reflection I agreed to stay

until September. Betsy left after a week having shown me how everything worked

and from which nearby springs (and not so nearby) drinking water was available.

I found out that, although Betsy was a fascinating person who had seen the island

before any development had started, she was not an easy person to live with,

and I was happier once she had left and the farm was all my own to manage as

best as I could.

Before she left, but was in Town shopping, 2 tearful children suddenly came

running up from a kalivi below, just next to the end of the airport. They were

calling for Betsy, but I managed to tell them that she was not there. They then

pleaded with me and more or less dragged me down to their kalivi. I didn't understand

what was going on but they obviously needed help. It turned out that one of

their younger brothers had been kicked in the head by their mule and the father

was carrying him to Town to the Health Center, some 4 kilometers away. I jumped

into my VW and picked them up and drove them to the Health Center. The boy,

Georgos, was OK after being bandaged up, but my reputation as someone who would

help, was made :-) Another of the brothers now helps me put my boat mooring

in every year, and his wife is the secretary to my accountant. We go out for

tsiporo at least once a year and the story gets told anew.

I slowly got into the routine of Betsy’s and Greek peasant life in general.

Every morning was feeding and cleaning out the chickens and the rabbits, dragging

the donkey out of her shed to a bit of grazing, and pumping some water for the

vineyard. There was a large water tank with a concrete collection apron around

it, where the winter rains were gathered for summer use. This was then hand

pumped to a couple of 50 gallon barrels for distribution by bucket to each vine.

There were13 rows of grapevines that needed watering once a fortnight. The water

in the reservoir on her land was scarce and precious. I had to pump it by hand

into the 2 barrels by the vineyard and then take it by bucket to each vine and

measure out 4 kilos, no more, no less. (The Greeks do most things by weight

so it was kilos of water, not litres, and one still orders wine from the barrel

in this way.) The reservoir looked out over the airport, Xanemos Beach, Cape

Kefala and Skopelos and every morning and evening I spent roughly half an hour

pumping and meditating (you could call it) whilst enjoying one of the finest

views in the world. I did one row per day and on the 14th day I (the god of

the vineyard) had a day of rest. It was the day that I would go down the mountain

(as I thought of it then) and visit my friends.

Living very much alone (except for the animals) and just going to town once

a week for supplies and once every other week to visit, threw me very much back

into myself, and I had the time to have a good look at my life and evaluate

just what (if anything) I wanted to do with it. Up to this time I had drifted

along. I had given up working with computers and all other kinds of “normal”

work, as it just didn’t seem to be satisfying in any meaningful sense.

Having the small financial freedom of my inheritance and the massive spiritual

(if you like) freedom that I found at Betsy’s started me thinking that

I had found some way of life that really suited me. It gave me the freedom from

social mores (and the British “class” system) that I had always

craved, and (as a foreigner) gave me the freedom to just “be myself”

without fitting into anyone’s preconceptions of who I should be. The fact

that Skiathos was (and still is) to me, a paradise, also helped me to start

thinking seriously about taking what little capital I had and, instead of blowing

it on a round the world trip (which would still have been a great education),

investing it in a piece of land and trying to live here. All this evolved over

the months I spent at Betsy’s and I shall always be grateful for the wonderful

time I spent there, and Betsy’s, albeit unwitting, influence. I had learnt

how to load a donkey (or in fact any four legged beast of burden), make water

stretch a looonnng way, grow things, care for animals, care for myself (!),

not rely on so called civilization but more upon myself and friends and, in

short, discover my own worth and value as a human being.

Living virtually on my own with only Greeks as neighbours, I needed to rapidly

learn Greek so that I could understand what they were saying to me (and if it

was nice or not!). Greeks are extremely hospitable to strangers (it can change

later as the friendship becomes real, or remains just superficial) and everyone

I met was very helpful and friendly. They were also curious as to why this long-haired

“freak” was living in the same way as they did, when everyone knew

that foreigners were all rich and could eat off gold plates. Betsy, by then,

was accepted as a “local” but still a bit of a weirdo, but I was

seriously outrageous looking and this was something to be discussed, mulled

over and researched by devious means, mostly alcoholic. I had many conversations

whereby I would point at something and say, “glass” to which they

would say, “potiri” and then, “wine” to which they would

reply, “retsina” or “krassi” and then we would toast

each other, fall off the chairs and I would discover the word for “drunk”,

“methismeno”. Having learned “potiri”, they then delighted

in confusing me by saying “krassopotiro” (wine glass), “ouzopotiro”

(ouzo glass), “neropotiro” (water glass), etc. I discovered that

there are at least three different words for the almost everything and they

would use one of the ones I didn’t know just to stoke me up. The Skiathitees

have their own dialect that tends to cut the end off words so that, whenever

I went to Athens and proudly tried out my newly learned Greek on a shopkeeper

or hotel owner, they would look at me blankly and reply in German!

Greeks are also very tactile (there are no really world famous Greek painters,

except the one who went to live in Spain, but their statues are amazing) and

they “speak” with their hands and bodies. If you are observant (as

I like to think I am) you can understand so much of their conversation by watching

as well as listening. My Greek is still not as good as it should be after all

these years but I can often understand a long-range conversation that I cannot

hear.

During this summer I wrote to many friends and acquaintances to tell them about

“my paradise” and to invite them to come and stay, as there was

enough room at Betsy’s for a few guests. Of all the people I contacted

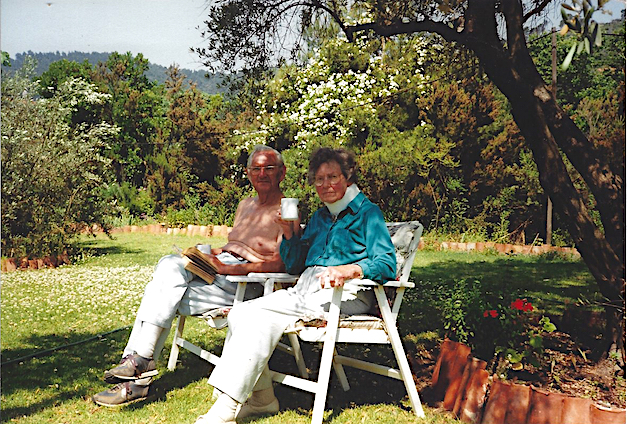

only Annette and my parents, Jim & Eve, came to see me.

Jim & Eve (quite many years later)

Annette and I sorted ourselves and relationship out (but not without a little

more heartbreak on my side) and that helped to clarify for me that the idea

of staying in Skiathos was definitely better than returning to “normal”

life. My parents (who I think had rather despaired of me ever settling down

or “coming to anything”) came to see just what I was raving on about.

They realised that this was something I was very serious about and gave me support

and encouragement (even though I think that this was extremely hard for them

to do so). They subsequently spent many holidays with us and their grandchildren

here and I am sure they were glad not to have tried to dissuade me.

I also met many interesting and wonderful people in that first summer. People

like Irini a beautiful, young Greek lady who had just qualified as an architect

and was building a villa for her parents on the Kalamaki Penninsular.

Geof & Irini at Reese's

She had been coming to Skiathos every year since she was a young girl and is

still coming to this day. She was having a fling with “American”

Jeff, a friend of Keith’s who also stayed that summer. I well remember

a party at Jeff’s kalivi when Franz who, having been born in the desert

in South Africa and could smell rain two days away, led us all in a rain dance

around the olive trees by moonlight. In fact, Franz used to make money by betting

with the Greeks (they love a gamble) that rain would come in two days time and

he was right nearly all the time.

My friendship with Keith and Paula deepened and I came to admire and like Reese

and Patti immensely. Many travellers passed through and left both good and bad

memories but always more experiences to add to my “new” life.

(from the left) Annette, me, Patti, Reese and Reese's mother, Bess

I met a (slightly eccentric, if not “mad”) German psychiatrist,

Hannes, and his wife Heidi who was a well known German actress and quite beautiful.

The day we met, I am sure Hannes was on something (probably acid) as he was

describing a film he wanted to make but the story line just rambled from one

crazy scene to another. I went with them some days later to see a piece of land

in Alonissos that was for sale and I liked their company a lot although his

ideas were weird to extreme about all aspects of life. I was open to listening

to anyone and their opinion at that time, trying to soak up as much “life”

as possible.

Other notable meetings were with Babis, who was building Irini’s villa

and eventually first showed me Zorbathes. His mother Areti (also the mother

of Stathis, of taverna fame), who had had 9 children and still looked after

one who was a bit “soft in the head” even though she was by then

well over 70. She made the most wonderful tyropittas (country cheese pies) with

eggs, milk, home made feta cheese, pastry rolled out to paper thinness, and

a cheerfulness that belied her hard life and added to their flavour. Stathis

still makes these (but only for friends) and they are just as delicious. She

could remember growing up in Kastro, the old town of Skiathos, and how, when

they moved, they took the doors, windows and roofing materials along to make

their new houses. This is one reason why Kastro looks so desolate with just

ruined walls standing.

I used to get drinking water from a spring below her kalivi, which welled up

inside the bole of a large plane tree. I loaded the donkey, called “Donk”,

with various metal and plastic containers to fill with water and trundled down

to the tree. Areti would hail me and I would tie up Donk and sit down for a

cup of Greek coffee (actually Turkish but never mention that!), a piece of pie

and a chat in my broken Greek and her descriptive hands.

The whole pace of life was just so different from “so called” civilization,

and all the hurry, stress, drinking and drugs that compensate for the lack of

the “real” civilized society which I definitely thought I had found

in Greece. Needless to say, Greece has been rushing to join the first type of

life with its seeming economic benefits but has lost a fair amount of her soul

in the process…you don’t get something for nothing! I found myself

changing from a confused, often doped, child of the middle class suburbs in

which I grew up, to someone who cared for other people, cared for some deeper

values than simply material ones, and generally felt almost completely at peace

with myself and what I was doing.

It’s about time that I described Skiathos a little. It is a relatively

small island, tucked in the lee of the Pelion Peninsular and not subject to

the same strong winds that howl down the Aegean and through the Cyclades islands

for most of the summer. The prevailing wind is northeast and rarely blows more

than 4 on the Beaufort scale. Ideal for sailing! Skiathos is blessed with fertile

land, lush green forests and many sandy beaches. There are at least 18 long

beaches with beautiful sand plus another 40 or so smaller sandy beaches. There

are also 4 large pebble beaches including the famous Lalaria Beach with its

smoothed pebbles and crystal clear water. When I arrived, there was only 1 tarmac

road from Skiathos Town to Koukounaries Beach plus the mud road leading to the

monastery of Kounistra and the beach of Aselinos. Everywhere else was accessed

by foot or animal and these paths were beautiful. The main ones, like the one

from town to Kastro had been laid with large cobblestones for their whole length

and had been worn smooth by the constant tread of hoof and shoe. It took around

3 hours to get to Kastro on this road and it passed fairly close to the highest

point of the island at 433 metres. In olive picking years (every second year),

people would set out at 3 o’ clock in the morning to be at their land

at Kastro or Kechria so that they could start picking the olives at first light.

They would stay for several days in tiny kalivis whilst sacks of olives were

carried back by animal to the olive press situated in Skiathos. I loved walking

these old trails and we often took picnics with us and went off for the day

to some remote part of the island. Skiathos seems to have so many different

facets to it. In many places, there are mini-climates and one half of the island

is definitely different from the other. This seems to be geological as the eastern

half has more granite in it and the western half is mostly sandstone. The olive

trees on the eastern half grow better and produce more oil per kilo of olives

than those towards the western end. It is often the case, when we have thunderstorms

that it will pour down with rain on one half of the island and there will be

virtually nothing on the other half. The dividing line seems to run from the

Kalamaki Peninsular through to the Kechria Valley.

There was very little tourism then. It was mostly Greek people who would come

in July and August and for the rest of the time, Skiathos Town was a sleepy

little fishing port. When the ferry came in, once a day, it was a big event

and half the locals would go down to see what was happening and who, if anyone,

was arriving.

The foreigners living on the island were split into two groups. The “villa

owners” who had bought villas on the Kalamaki Peninsular and the south

side of the island, and the “kalivi dwellers” like myself who were

mostly hippies, travellers or odd eccentrics of one sort or another. (In the

late 60’s a South African man saw the potential of Skiathos’ beauty

and started buying up plots of land on the Kalamaki peninsular, mostly around

Kanapitsa Bay. He offered a plot for £2,000 and a plot complete with villa

for £4,000! Although this was quite a bit of money in those days, the

villas were still bargains and are now worth many, many times their original

purchase price.) Mostly the first groups were British with a few Germans, Greeks

and a couple of other odd nationalities as well. They were well off, or rich

retirees, or remittance men. The kalivi dwellers were largely struggling to

make ends meet so that they could continue to live in this wonderful place.

The one group was often a source of income for the other and, although there

were some “class” divides and, obviously, economic ones, we were

all foreigners here (even the non-Skiathitee Greeks were “foreigners”!)

and therefore held that in common. The locals were, on the whole, very friendly

and hospitable and were always encouraging whenever I tried to make myself understood

in my (very) basic Greek.

The beaches were mostly empty except for Koukounaries, which was then an umbrella

free, long, fine sandy beach with lovely Koukounaries (stone pines) behind it,

where one could relax in the shade. It had a taverna, as did Troulos Beach and

Kanapitsa Beach. All the other beaches were more or less deserted. Vromolimnos

Beach (for example) was covered in driftwood and rubbish from the sea and no

one would ever think of going there. We would get quite put out if we saw someone

else on our favourite beach of Platanias (now often known as Aghia Paraskevi

Beach) even though they might be sitting some 400 metres away from us!

When Gabi told me about Skiathos, I had envisaged a small Greek cottage by the

sea where all these friends of hers stayed. I actually saw a cottage exactly

like that when I went to live at Betsy’s but it was right at the end of

the airport and the owners (the people whose boy had been kicked in the head

by a mule) had been moved out. It looked very sad. The airport had just been

finished when I came. It had used (and put tarmac over) the best land in Skiathos

where everyone used to grow their crops and vegetables and grapes for wine.

This is not an unusual situation. Heathrow Airport (which I grew up very close

to) is reputedly built on top of 18 foot of prime Thames Valley topsoil. The

airport had broken the hearts of many of the old boys who had lived on that

land all their lives, raised their children there and grown their gardens and

vines, and although they received compensation (not much, I fear) many of them

faded away and died in the next few years. It has been a mixed blessing. Whilst

bringing the wealth that came with tourism, it was also the first step in the

erosion of a wonderful lifestyle that had not changed much for many centuries.

There were few fences. Land was defined by natural borders or stones set upright

at strategic corners. A person would identify his land as going from this corner

stone to that stone, along this streambed, up to the hedge and back to the corner

stone. This olive tree was inside but that one belonged to the neighbour, and

so forth. What fencing that existed, was usually around a kalivi to keep the

animals OUT and away from the garden. Chickens, goats, rabbits, etc. often roamed

free, particularly up in the hinterlands where the goat herders lived and the

nearest neighbour was a long way away. There were disputes about borders, of

course, and accusations of neighbours moving border stones were rife. There

was an incident I heard of (I believe it is true) where three brothers were

dividing up land inherited from their father and the dispute over the ownership

of one olive tree became so heated that eventually one brother held a second

whilst the third brother stabbed him to death! A “passionate” killing

like this was considered far less grave than premeditated murder and, often,

the sentence would be lighter than given to someone dealing in hashish, for

example.

Many, many years ago, long before I came, there were no written records of land

ownership and transactions. One family was the “records office”

and kept everything in their heads and this knowledge was passed down from father

to son. One assumes that this family must have been honourable otherwise the

opportunities for corruption would have been rife.

The town of Skiathos was built on two hills that overlooked the harbour. In

between the two was a streambed which had some water most of the year but which

had been covered by the time I arrived and turned into the street of Papadiamantis.

We still affectionately know this street as “the main drain”. At

the end of this street, next to what was the police station, were two massive

plane trees that provided lovely, deep shade. After the police station moved

there, for some reason, one was completely cut down and the other trimmed back

to a bare shadow (sic) of itself. Now, the tourist shops in that area have had

to put in air conditioning to keep them cool (which consumes energy and pumps

out more heat into the atmosphere)! The high school was there but in much older

buildings that nowadays. The junior school was on the Bourtzi and there were

not enough teachers to go around so some children went in the morning and some

in the afternoon. The town council had recently put on a causeway to the Bourtzi

so that the kids didn’t have to scramble across the rocks (and sometimes

get wet) on their way to school. Traditionally, all the youngsters had their

hair clipped very short in spring and I (who had been happy to get away from

“skinheads” and the like) found it a bit of a shame. At the beginning

of each summer, they were brought down to the harbour and, in front of the main

outlet from Papadiamanti Street; they all jumped in and paddled around happily

(something I would not recommend now!).

A small amount of people were making money from tourism and working for the

villa owners but most people still lived from the land, the sea, or received

money sent back from the local men working on the Greek ships all over the world.

Every morning, a line of horses, mules and donkeys would set out from the village

towards Koukounaries which would gradually get less as each rider peeled off

down some trail or other to get to his olive grove or small plot. Often the

animals would be loaded with 2 sacks of their own manure, scraped up from the

stable floor and destined for a couple of olive trees or a garden patch. Distances

were measured in cigarettes, i.e. “How far is to Kolios?” “About

2 cigarettes”. The old trails were kept open by a swipe of a machete from

horseback if some branch or twig became long enough to be bothersome. They would

return in the evening with their animal loaded with olive prunings for a goat

or lamb that was kept somewhere near the village.

A word or two here about the olive tree. Olives and olive oil has been the staple

of the Greek diet for centuries (you could follow the path of the army of Alexander

the Great through Asia by the olive trees that grew from the pips dropped by

the wayside). Both are full of goodness and olive oil is reckoned to be the

healthiest of oils. Visitors to Greece that think a dish of food that has a

lot of oil in it is “greasy” and likely to upset their stomach are

making a dreadful mistake! However, the olive tree not only provides good food

but also gives wood for heating (it burns long, beautifully and gives good coals

for cooking) and the leaves are a good source of nourishment for goats, sheep

mules, donkeys, etc. The trees provide shade for a midday nap and food for the

eye because the colours of the leaves are constantly changing as they rustle

in the breeze. An artist friend once told me that it s impossible to paint an

olive trees true colours on canvas because they never stay the same.

Olive trees will grow in places that most other trees would die in and will

cling to seemingly infertile, rocky areas, and thrive. They do need attention

but, with a minimum amount of fertilizer and a regular pruning, will produce

a crop of beautiful olives and golden oil. As the olives mature, from September

onwards, they turn from green, through purple to a deep black colour. At any

stage of maturation, if you pick and polish an olive on your shirt (much as

one polishes a apple), you will be rewarded by a glowing jewel as the natural

oil burnishes the skin. The trees have a natural two-year cycle and so every

other year is an “olive” year and the olive presses are spruced

up and repaired ready for the harvest. Even here, the olive proves generous

to the last. After the virgin pressing in the local presses, the left over semi

dry slurry (pyrini) is taken away by lorries to the mainland to large, commercial

presses which squeeze quite a bit more oil out. These same lorries bring back

the (now almost dry) pyrini to the local presses where it is burnt to produce

the hot water necessary to clean the oil after pressing.

Fishing was the other main industry and there were far more fishing boats then

than there are now. In the evening the “gris gris” boats, consisting

of one mother caique towing lots of smaller boats each equipped with acetylene

lights, would fire up their old diesel engines. They poured a bit of oil into

the air intake to increase the compression and then with a hefty swing on the

handle and a few smoke rings out of the exhaust, they would start with a “wump,

wump wump”. The mother boat would ease slowly out of the harbour and ropes

were thrown from it to the first small boat, then from that to the second, and

so on, until there was a string of boats progressing out to sea as the light

started to dim. There would be the odd spot of cursing and piss taking if someone

failed to catch his rope as the boats went passed. They would return at daybreak

and unload their night’s harvest at the fish market where eager locals

would crowd around, pushing and shoving to get the best of the catch. (Queuing

is an unknown phenomenon in Greece.) Smaller fishing boats would come and go

and often sell the few kilos of fish straight off the boat. There were also

one or two larger trawlers that would stay away for several days. A lot of their

catch would be sent off to the mainland packed in ice once the best fish had

been selected for local consumption.

The stretch of the waterfront from the plane tree (where Keith and I consumed

our tsiporos) to the fish market was where the fishing boats were moored. It

was not wide enough to accommodate shops and had a small “park”

and a few benches that were shaded by leafy trees in the summer but warmed by

the sun in winter. This was a favourite spot for the “old boys”

to sit, leaning on a stick (bastooni) and flicking some worry beads (komboloi)

back and forth in complicated patterns and rhythms. They would exchange gossip,

josh “youngsters” (60 or less) walking down to buy some fish, or

just sit watching the boats bobbing up and down next to the quay. In the winter,

it was a place to soak some of the sun’s warmth into old bones and doze

off for a while. I found myself contemplating old age (and its inevitability)

and thinking to myself that here would not be a bad place to get old in.

Just along from these benches were the public toilets, a place you would have

had to pretty desperate to contemplate approaching.

The fishermen spread their nets out on this part of the waterfront and sat on

the ground mending their nets with one gnarled big toe poked into the net to

stretch it out for sowing. They were always barefoot and usually had a cigarette

smouldering in one corner of their mouths as they worked.

From the fish market, steps led up to a maze of narrow streets that eventually

led to the top of the west hill where the Health Centre is located. This was,

and still is, the nicest and most authentic part of town. The narrow streets

do not allow much major building so the old houses remain pretty much as they

were and many have been renovated beautifully. Those close to the cliffs above

the sea have wonderful views over the harbour to the Bourtzi and beyond.

In the town (well, it was a village then) the men played cards and drank coffee

or ouzo in the kafenions and discussed, often in raised tones, the day’s

happenings. Greeks, from a foreign perspective, always seem to be very loud

and having arguments but we should remember that “drama” is a Greek

word and an event that has no dramatic appeal, or cannot be dramatized in the

telling, is not worth discussing. The purchase of a piece of “worthless”

land for a hotel in Koukounaries could be passed over in favour of a heated

discussion as to whether the saddle maker was justified in raising his prices,

or was he ripping everybody off (again!). The women sat outside their houses

and gossiped about this or that but, I believe, secretly ran the whole society

whilst the men, who seemingly ruled the roost, were actually given only so much

rope!

In the main street, opposite what was then the Post Office, was the “workers”

Kafenion. It was like kafenions you used to find all over Greece, with many

small, marble topped tables, each with 4 chairs, packed into the minimum of

space. Here the workers and haulage men used to wait for anyone needing their

services, drinking an early morning “cognac” (really cheap brandy)

and swapping stories and discussing anything from lack of work and politics,

to football scores and the latest local scandal. There was usually a “character”

(often well oiled with cognac or tsiporo) that would keep the company in stitches

with stories and antics. In the evening it became their local “Ouzeri”

where carafes of ouzo and tsiporo were consumed with the small plates of grilled

fish, octopus, baked potatoes and anchovies that prevented the alcohol from

getting too much into the blood stream. The small plates of food (mezedes) were

left on the table as they piled up, and when the bill was eventually called

for, the proprietor simply counted the number of plates to calculate the cost.

Work for the following day was often arranged during the course of the evening.

Many foreigners complain about the size (or lack of it) of ouzeri and kafenion

chairs. They are uncomfortable to sit on for a long time but not if you use

them as the Greeks do. You need three (3!) chairs to sit on. One you actually

rest your bottom on, another in front of you for one foot and one to the side

of you for your arm! This is remarkably comfortable. Of course this no longer

becomes tenable as the room fills up but by then you normally have good “parea”

(company) and a few small drinks under the belt and you cease to notice the

chairs at all. The Kafenion was pretty much a male bastion. Women were allowed

but frowned upon and Lida never felt totally comfortable there. It eventually

closed down as the rent became too high for a small local business and it is

now a shop selling gold and silver jewellery. A real shame as it was another

part of the “old” Skiathos that I love and miss. There are still

a couple of similar places in the back streets that only the locals use but

they don’t really have the same atmosphere of that original one.

The women always greeted me pleasantly as I walked past and it was not difficult

to smile at everyone I met. Only one of the priests would not say hello to me

and avoided my eyes. I guess he felt that long hair and a beard was his prerogative

and he resented me wearing both. I finally received his acknowledgment, many

years later, when he wanted to buy some of the organic green beans that I was

then selling in the town, and after that, he was OK. I was always careful to

give the people of Skiathos their due and respect and found that it was then

returned to me. It seemed that, the more I liked Skiathos, the more it liked

me.

The big social occasions were the religious festivals when the islanders would

gather at this or that church, some inside participating in the service but

many outside with a flagon of home made wine and a picnic, thoroughly enjoying

a party. There is a commemorative headstone in the churchyard of Agios Yiannis

Prodromos (John the Baptist) close to Kastro, which states that 4 people were

struck by lightening on that spot and died. One wonders if they were having

too much fun outside whilst the service was going on? Marriages and christenings

also afforded an excuse for a good time and name days were celebrated by the

person whose day it was plus all of his family (which didn’t leave many

people to do any work, so most didn’t!)

Easter is THE Greek holiday. It is usually preceded by 40 days of fasting when

meat is definitely proscribed and even olive oil(!) must not be eaten on certain

days. Most people in Skiathos did some kind of fasting, some sticking absolutely

to the letter of the Church law whilst others didn’t eat meat but did

eat everything else. Services are held every day for the last week leading up

to Easter Sunday, the biggest of these being on Good Friday night when the “Epitafio”

(bier) of Christ is carried around the Monastery of Evangelistra with a huge

crowd following. Tradition says that it always rains that night as God weeps

for his son. Surprisingly enough, it often does. On Saturday night, there is

a big service in the main church of Tries Iearachis (the lower of the two in

town) and everyone gathers there to welcome the coming of the light as Christ

is resurrected. Towards the end of the service, the priest chants “Christos

Anesti” (Christ has risen) and lights a candle from the one candle that

was burning all through the service. The worshippers then light their own candles

from this one and pass the flame on to their neighbours. The light spreads throughout

the church and then into and through the church square and is really a marvelous

sight. Everyone shakes hands or kisses and repeats “Christos Anesti”

as they pass the flame on. The candles are carefully shielded as everyone walks

back to their houses and then a cross is described in black smoke from the candle

above the doorway to bless the house for the following year. Those that live

out of town will be seen driving home with the inside of their cars lit up by

the candles. A traditional meal of “Mayeritsa” is used to break

the fast after the service. This is a soup made from the intestines, liver and

heart of the lamb or kid that will be roasted on the Sunday. On Sunday morning

early the men get up early to start the fire to make charcoal for grilling the

lamb or baby goat that is traditional for Easter. Often “Kokkoretsi”

will be made on a smaller side spit and will be eaten as a meze to keep hunger

at bay as the main meal will always take many hours to be ready. Kokkoretsi

is all the internal offal (liver, lungs, spleen, kidneys, etc. from the lamb

or kid) threaded in small pieces on a small spit and then wrapped in the small

intestine of the animal. This may sound disgusting to some but it is in fact

a delicious starter if you can get over the prejudice against offal and guts.

The animal is spit roasted over the coals and basted with oil, lemon and oregano.

Three lambs roasting and a skewer of Kokkoretsi

This is a long, hot, thirsty job and some will be pretty high on wine or beer by the time their lamb is done. Boiled and coloured Easter eggs are cracked, one on top of the other to see who has the “best” egg (the one that didn’t crack), and then everyone sits down to a huge feast of meat, bread and green salad. The afternoon is often spent repenting!

Betsy returned and I had to think what I should do next. The idea of buying

a small piece of land and living somewhat like Betsy did, had slowly crept into

my head during my stay at her place.

Still, part of me was saying that if I was going to invest in land, I really

should do it in England. After all, that was my real home, wasn’t it?

I decided to go back and look at the possibilities.

I traveled back with Pat and Collette, a lesbian couple who were going as far

as Munich and I stopped there for a couple of days and visited Hannes and Heidi.

Returning to the UK, I discovered just how much I had changed (and how little

it had) and how I could never possibly live back there again. I had seen too

much other beauty, too much good weather, too much hospitality, too much freedom

and too much of my own heart to ever want to return to my land of birth.

I returned to Amsterdam and visited friends there and talked about my previous

summer’s experiences.

I often visited Pax, a Dutch Indonesian who had a flat where many people visited

and crashed and where I had first met Annette. The previous winter I had also

met Adri and Lida (then married) and two of Lida’s sisters, Liesbeth and

Julia. It was Julia who had said to me after I had split up with Annette,”

Nooit vergeten, achter the wolken, schijnt altijd de zon”, which translated

means, “Never forget, behind the clouds, the sun is always shining”,

and it had been this little expression that I had carried with me to Greece

and found to my delight, to be true. I spent quite a bit of time with Adri and

Lida and liked them both immensely. Adri and I had marathon chess games that

often went so deep into the night that Lida could be waking for work before

the game was completely finished and analysed.

At Pax’s I met Walt, a friend of American George, who was interested in

traveling to Greece. As I said I was going back to Skiathos that January, we

agreed to travel together and share expenses. Another old friend, “Canadian”

Chris would come with us and the three of us crept out of Pax’s flat one

afternoon (without saying goodbye, it has always been the hardest thing for

me to do) and drove south towards Germany. When we got to Munich, I got a bad

dose of flu so we stopped at Hannes and Heidi’s house while I recovered.

Chris decided at this point that he really didn’t want to go to Greece

and left to go back to the UK. Heidi and I had a small fling but it wasn’t

anything serious.

Walt and I drove down through Yugoslavia and took the coast road. This was beautiful

in a rugged, barren kind of way but also took forever as the road wound in and

out following the coastline faithfully. The weather was very mild and we even

slept out on a beach one night. At Dubrovnik we started inland to connect with

the main highway at Skopje. This involved going over the mountains and, although

the days were sunny and bright, the nights became seriously cold. We would wake

up I the VW van with frost all over the inside of the van and would have to

light the gas cooker to melt it. Of course it melted all over us and our sleeping

bags just to make life a little more “interesting”. Our first stop

was for coffee and bread at the nearest hostelry which usually consisted of

a big room with a few tables and chairs and a massive wood burning stove, hand

made from an old oil barrel, around which everyone would cluster. Both of us

had long hair and fairly flamboyant clothes and we were looked upon as some

apparition from…who knows where? As we had no Serbian, we did a lot of

smiling and nodding as we were bombarded with questions about (presumably) who

we were and where we were going. It is a very strange feeling not to be able

to speak to other people but I discovered that a smile goes a long way wherever

you are.

We arrived in Greece and I must say, it felt like coming home.

<Back to contents> <Next chapter>