<Back to contents> <Next chapter>

10 - ANIMALS

My lifestyle in Skiathos was to become inextricably caught up with animals

of one sort or another.

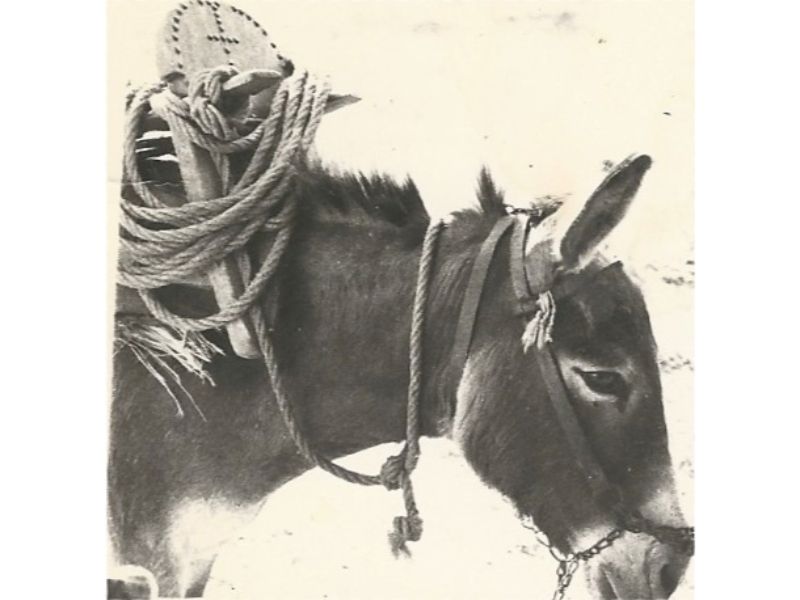

At Betsy’s, I had to feed and look after chickens, rabbits, cats, dogs

and her donkey, known (semi-affectionately) as “Donk”. I would take

her down to the road to carry back my weekly shopping and use her to carry the

drinking water that I dipped from a spring in the trunk of a plane tree. She

was possibly the slowest donkey in the world and, if I was day dreaming or got

wrapped up in the fabulous views from the donkey trails, she would go infinitesimally

slower until we had almost ground to a halt without me being aware of it. She

loved the spiky tops of a type of thistle that grew along the paths and would

suddenly swerve off to harvest a particularly large one. I never really felt

that I was in control of her; she just let me use her occasionally.

The second time I stayed at Betsy’s, during the winter of my second year,

I also had my own donkey called Francine, that I had “inherited”

from Reese and Patti (via American Jeff and Keith & Paula) who no longer

needed her once they had acquired their horses. Francine belied the sweetness

of her name by being the most vicious donkey in the world. I had never heard

a donkey growl before, but Francine did, and meant it! She was also one of the

quickest. She only accepted me as “the boss” after I had lost my

temper with her and thoroughly beaten her up. After that she was fine with me

but would attempt to kick anyone else who got into range. She booted both Adri

and Lida’s brother in law (big Dutch men and certainly not midgets!) into

the bushes off the trail when she was fully loaded.

Francine

I had to gather firewood to heat Betsy’s through the winter and often

went down a steep path to the nearest beach to pick up driftwood. Coming back

up the path, I either had the choice of having Francine in front (going at a

rate of knots) and Donk behind (going virtually backwards) or vice versa. Either

way, I would either be stretched between the two or crushed between the two

and I sometimes wondered if they weren’t getting some malicious pleasure

out of the whole thing.

A little digression here to praise the Greek donkey and horse saddle. It is

not great for riding on, except side-saddle, but once you have learnt how, you

can load almost anything on to one of them. We have carried everything from

sand and gravel, bags of shopping and even 6-metre-long chestnut beams on our

animals. In fact, all the materials for our first house were brought to the

site by this means.

Mavrika & Francine

By the time I was building this house, I had inherited Keith and Paula’s

old horse called Mavrika (“little black one”). She was a sway backed,

reasonably sweet natured old nag of indeterminate age, who had an aversion to

work and snakes. When she first saw the pile of chestnut beams and pine planks

that had to be carried 1 kilometre from the road to the place where we were

going to build our house, she rolled on her back and whinnied, “colic!”

Because she was prone to getting colic, particularly if she ate figs, I believed

her and spent the rest of the day walking her around in circles so that her

guts could clear. When a horse gets colic (a swelling of the stomach with gas

which closes off the possibility to get rid of the gas and can be fatal) you

have to make sure that they don’t lie down because there is then no possibility

to clear the blockage. So, we walked “Mavi” around and around until,

with incredible wet farts, she finally vented the offending (and offensive smelling)

contents of her stomach. The following day she tried it on again but this time

I didn’t believe her and she carried poles and planks all day without

mishap. Whenever she saw a stick or bit of rope on the path, she would refuse

to budge until I had taken it away (therefore proving that it wasn’t a

snake) and assured her that everything was OK.

Her true nature was exposed when, returning from sampling (rather a lot of)

retsina with a local goatherd, I loaded her (with great trepidation) with 2

sacks of cement totalling 100 kilos. The goatherd said, “What just 2 sacks?”

and threw another one on top. I expected Mavi to collapse, but when he clicked

his tongue at her, she realised she was dealing with a Skiathitee (and not a

bunch of soft foreigners) and RAN all the way home.

She used to suffer dreadfully from horseflies during the summer and there was

not much to do about them except immerse her in salt water, i.e. the sea. She

was not awfully fond of this and, taking her one day to Aselinos (the nearest

beach), we provided much amusement for a group of tourists who were sunning

themselves on the beach as we struggled to get her into the water. However,

when the flies were deprived of their supply of blood as we and Mavi sank slowly

into the waves, they decided to head for the nearest alternative source. The

last we saw of the tourists was them running down the road being pursued by

a cloud of thirsty horseflies.

Goodbye Francine

Francine disappeared when I lent her to one of our neighbours for the winter

whilst we were away in Amsterdam. Upon our return, we were told that she had

been lent to my neighbour’s mother on the mainland but would be back soon.

Needless to say, she never came back and after some months, I just stopped asking

about her. That winter a very basic dirt road had been bulldozed through Zorbathes

and we didn’t really need 2 animals any more. In fact, we hardly used

Mavi for work any more and she spent the last few years of her life eating and

relaxing until she finally got a bout of colic that we couldn’t shift

and died. She had had a good retirement and we missed her, but it was the right

time for her to go. I can’t say we really missed Francine as she made

Lida and all our friends and guests extremely nervous, to say the least.

At one time or another, most of our neighbours have kept pigs. “Kept”

is a euphemism as they often didn’t have sufficiently strong pigsties

to keep them in, particularly if they hadn’t bothered to come and feed

them. Our nearest neighbour, who had helped us tremendously in our first years

and had become quite a good friend, was driving a taxi one summer and therefore

just didn’t have time to look after his pigs (some 30 of them). They were

constantly breaking out and often I fed them with grain intended for our goats

to lure them back inside. One night, we came back from a party to find that

the pigs had broken into our home and had spilled (and drunk) our homemade wine,

our olive oil and eaten our home-made bread. There were even trotter marks on

our battery-operated record player, and it was obvious that they had been partying

too.

I fetched the neighbour the following morning to show him the damage and his

only comment was, “Never mind” followed by the Greek shrug which

means, “What can you do”. He offered to pay for the damage but never

did and our relationship started to deteriorate from that time. It finally reached

the point of me threatening to take him to court because his goats (he was then

into goats) were destroying our trees and plants. It seemed to work as his goats

disappeared, but we barely nodded to each other for quite a while. You do not

threaten someone with court action lightly in Greece! Probably in a few more

years we will be talking again and maybe even reminiscing as that is often how

things go here.

For several years, we kept a pig ourselves, fattening him up for Christmas with

the waste from the organic garden and a supplement of bran, so that we had a

source of good chemical free meat for the winter months. Two local Greeks had

started a pig farm next to our land (fortunately downwind) and, because they

had no water, they took water from our old well. In exchange for this we got

a nice piglet every spring. Our pigs always enjoyed a great life, were treated

well and became our pets. They are at least as intelligent as dogs and probably

more so. We gave them a lot of room to move in and, contrary to popular belief,

they are extremely clean animals using only one section of the run as a toilet,

and never fouling their food or the rest of their area. Only when man confines

animals do things get out of kilter - and then we blame the animals! A bowl

of bran was given to them at slaughtering time and they hardly noticed as they

were killed.

One of our pigs was constantly bothered by one of the neighbour’s chickens

which used to hang around and pick out the odd bits of bran from his feeding

bowl when he had finished. The pig used to watch the chicken with a scowl on

his face until finally one day, it all got too much for him, and with one “hap”

of his jaws he grabbed the chicken and ate her whole, feathers and all!

Some years ago, we had around 140 litres of wine happily fermenting away, and

we were licking our lips and rubbing our hands in anticipation, but that was

before another of our neighbours 2 pigs decided that they would have a "wine

tasting".

What happened was that the pigs had escaped and were obviously very thirsty.

They arrived on our lawn and were grubbing in the wettest part (where the sprinkler

overlaps) when one of them discovered the wine fermenting on the patio and managed

to put a neat hole in one of our 25 litre demi-johns with its snout.

Lida arrived home some time later to find 2 completely sozzled pigs lying on

the doorstep! She managed to drive them up the hill to upper neighbour’s

house (with the greatest of difficulty, they were stumbling around all over

the place) and shut them in his courtyard. I arrived shortly after and asked

what had happened as it was obvious via our "pig aerated" lawn that

something was out of the ordinary. Lida explained and I then realised that the

pigs belonged not to the neighbour above, but to another neighbour further down

the valley. Up we trudged and tried to move the pigs out of the courtyard and

down the hill before he came home and discovered them. They were, by this time,

suffering severely from the effects of some 20 odd litres of very young wine

and were most reluctant to move anywhere. After chasing them around in circles

for half an hour, we finally managed to get them going in the rough direction

of our lower neighbour and then sat back exhausted from our efforts. We informed

him what had happened, and he found the two of them the next day, crashed out

under some bushes (presumably with the porker equivalent of a huge hangover!).

In our second year in Zorbathes I took a trip to Volos to buy various bits and

bobs and to get a few chickens to start a flock. I went to see one of the chicken

sellers who always gathered outside the railway station with their trucks full

off cackling birds. I purchased four hens and asked if he had a good rooster.

Of course, he said, he had the world’s finest rooster but unfortunately

it was at back at home. I paid him for the four hens and the rooster, and he

agreed to take them all to the trading caique that was due to come to Skiathos

the next day. When I went to pick up my chickens the next afternoon in Skiathos

(it took 6 to 7 hours for the old caiques to make the trip) I found my birds

almost dying of thirst in the sun on the deck and a rooster surveying me with

only one eye! He (inevitably) was given the name of “Nelson” and,

in fact, turned out to be a magnificent rooster who kept all his “ladies”

in line and all their eggs well fertilized. He just didn’t like it if

you “crept up” on his blind side and would get his feathers all

ruffled. We gave all the hens names as well but the only one that sticks in

my memory was our first broody hen called “Margaret Hatcher”. Nelson

was the first of our chickens to be cooked (this was after his offspring had

grown up and supplanted him) but we didn’t realise just how tough a true

free-range bird could be. Although we pressure cooked him for many hours, eating

him was like eating chicken flavoured chewing gum and getting him down was a

real effort. The following day we all had the most horrendous farts which we

christened “Nelson’s revenge”!

We kept goats for quite a few years after we decided to live permanently in

Skiathos. Because, officially, we were not allowed to work, we thought that

we could make some income from raising baby goats and selling milk, cheese and

yoghurt to friends and villa owners. We slowly acquired a small herd buying

a few goats here and there, and then keeping some of the offspring. To buy Cleo,

our first goat, we had gone up to almost the highest part of the island at “Katavothros”

to visit our goatherd friend (the one who had loaded Mavi with the three sacks

of cement). He, his wife and daughters lived in a tiny kalivi on a plateau just

beneath Karaflidzanaka and Mount Mitikas (at 433 metres the highest point in

Skiathos). They were a “volatile” family and would have screaming

arguments that looked like they were going to kill each other but, apparently,

that was just a normal way of life for them and no serious violence was done.

I had met him in Larissa jail when visiting Keith and Paula before their trial.

He was accused of murder (but loudly proclaimed his innocence) and was acquitted

at his trial because the only “evidence” against him was that the

father of the murdered girl (a neighbouring goat herder) had simply said, “He

must have done it!” Unfortunately, he had had to sell many of his goats

to feed his family and pay for lawyer’s fees, etc. whilst he waited many

months for his trial. The murderer was never found. He arranged to take Cleo

behind his horse to a point closer to Zorbathes where we picked her up, tethered

her behind Francine and dragged her (literally) back home. She didn’t

want to go off with us strangers and, being a herd goat and never tethered,

was not happy with her halter and being forced to go in a specific direction.

All of this took a few days, a fair amount of retsina, a lot of shouting, some

singing, consumption of vast amounts of food and some heavy bargaining. We were

undoubtedly “ripped off” but the experiences we had more than made

up for that. That is the Greeks for you; they will take from one hand whilst

heaping genuine gifts and kindnesses into the other. We next bought another

goat, “Maria”, from one of our neighbours but neither of these two

gave a lot of milk. We were told of someone selling a “super milker”

in the next valley over. When we went to look at her, she obviously hard large

udders with a lot of capacity so we thought she would be a good addition to

the “herd”. However, she also had a swelling on one of the udders,

but the seller told us it was “no problem”, so we bought her. (When

a Greek says, “No problem”, watch out!) We called her Gertie, the

same name as one of my grandmothers, but they bore no resemblance to each other.

Gertie did, indeed, produce a lot of milk, but the swelling on her udder kept

getting bigger and bigger! I didn’t know what to do but thought I had

better ask “Barba” Mitso who was our fount of all knowledge regarding

husbandry.

Barba Mitso and his wife Elena were the only other people living in the valley

who were an old couple who kept around 20 sheep, a goat or two, a few olives

and a vineyard. “Barba” means “Uncle” in Greek but is

also a term used for older people who you respect but are not related to. They

were completely uneducated and illiterate and Elena, who was mostly sweet (but

could be fearsome), was fairly simple in her thinking. Her idea of explaining

something that we could not understand was to shout it louder and louder until

we nodded and smiled as if we did understand. Barba Mitso was cleverer and would

see immediately that we hadn’t comprehended something and would search

for other ways to describe what he wished to get across to us. As we were desperately

learning how to live the kind of life they had lived for all their lives, we

were constantly asking them many things. He would come by with his sheep and,

with a twinkle in his eye, ask us what on earth we were up to now, as we tried

to master another facet of “self sufficient” living.

Many evenings we went up to their kalivi to sit in front of the fire and listen

to their wisdom and folklore. The kalivi was about 1.5 metres wide by about

3 metres long (in other words, tiny) but they lived in there quite happily.

Sometimes, when their son and family came to stay, there would be 6 bodies inside!

A fireplace took up one corner and it was here that Elena did all the cooking

on an olive wood fire. A small round table took up most of the rest of the space

between the bed and the fireplace, but this could be hung on the wall when extra

room was needed. Seating was on “skamnakia”, traditional low wooden

stools upon which one squatted rather than sat. Whenever we visited, a cup of

Greek coffee was brewed in the traditional style, which meant that the water

was first boiled, sugar and the finely ground Greek coffee were added. Then

it was slowly brought to the boil again, inspected and brought to the boil one

last time to get a “cream” of bubbles on the top. This was then

poured into tiny cups and the first sip had to be drunk with a “slurp”

followed by a long “Ah!” of appreciation. (Although Greece is a

very relaxed place and very informal, this coffee ritual is probably as important

to Greeks as the Japanese tea ritual is to the Japanese. It certainly used to

be. Nowadays, in the cafes on the waterfront, “Greek” coffee is

often made hurriedly using the steam-heated water from the espresso machine

and bears no resemblance to the real thing. Look for the place where all the

locals are drinking coffee early in the morning, that’s where you will

get the genuine article.)

Barba Mitso would always listen to the news on a battered transistor radio (their

one “luxury”) and give comments on it to Elena and would try to

describe really important bits to us. Things like, “the Turks are up to

no good again!” were easy to understand but the ins and outs of Greek

politics were completely beyond us.

Elena showed us how to do the weekly wash by taking a large kettle down to the

vouthana (pool) in the streambed, filling it with water and heating it over

a fire made from dry twigs and branches that lay beneath the plane trees. Once

the water was hot, it was put into a large wooden tub with sloping sides where

the clothes were scrubbed. Rinsing followed and the clothes were rung out by

hand then taken to a breezy spot to dry in the wind. One year, we bought a wringer

(operated by turning a handle) from Holland, and this was considered the height

of sophistication by Elena (but denigrated as not really being “up to

the job”). Once, as I was stoking the fire for hot water, Elena told me

that Lida was a “good woman” and that if I were to mistreat her

or run away, she would find me and shoot me with Mitso’s (very old) shotgun!

Needless to say, it is only this threat that has kept me together with Lida

all these years ;o)

Being a shepherd and having lived around animals all his life, Barba Mitso was

our source of information about all aspects of keeping animals. We learnt from

him and Elena how to feed goats, milk them, help them to give birth, make cheese,

yoghurt and other milk products from their milk, and generally everything else

that went along with animal husbandry. We always consulted him when our animals

looked poorly and he usually had some herbal remedy to suggest or, in some cases,

would tell us not to worry. The strangest “cure” he used, became

known to us forever as “the day Barba Mitso blew up Gertie the goat”.

As mentioned before, we had acquired “Gertie” from an acquaintance

of a neighbour, and she was a good milker but had a slight swelling on one of

her udders. Over the course of time, this swelling grew and we started to become

concerned; even thinking that it may be cancerous. Barba Mitso was called in,

took a look and said, “Go to the Pantopoulio (little shop that sells everything)

and get a hoofta (handful) of barouti.”

When questioned about what “barouti” might be, he was either unable

or unwilling to explain it to us. Off we went to the Pantopolio and when we

asked for “barouti” were given a small paper bag with half the contents

of shotgun shell, the gunpowder half! “This is barouti?” we asked.

Yes, that was “barouti”. We took it back to Barba Mitso who then

asked for a plate and some matches. Everything was taken to Gertie’s stall

and he told us to hold her head. He placed the plate under the udder with swelling

and then took out his knife. “Oh my God” we thought, “he is

going to cut her open!” But no, he merely made the sign of the cross three

times in the air with his knife next to the swelling. Then he sprinkled the

gunpowder in the plate underneath Gertie, and we thought, “Oh my God,

he is going to blow her up!” Suddenly he lit a match and threw it on the

gunpowder. We expected an almighty explosion (forgetting that gunpowder needs

to be compressed to explode.) There was simply a flash and a large puff of smoke

(rather like the original flash guns for cameras) and the three of us (Gertie,

Lida and me) leapt up in the air in surprise. He then gave us his toothless

grin and said, “She’ll be fine now.” A few days later the

swelling broke open and the fluid inside began to seep out. The ignited gunpowder

had singed the skin of the udder (but not hurt Gertie) and made it brittle enough

to stop it stretching and so allowed it to naturally open. We merely kept the

wound clean and within a week Gertie was back to normal with only a small scar

to show for her trials. We, however, were traumatised for life! This became

known as, “The day Barba Mitso blew up Gertie the goat”.

We borrowed the use of a Billy goat in August and he impregnated the three goats.

When they gave birth, we decided to keep Gertie’s two kids who we named

“Titi” and “Nou Nou” which were the brand names of tinned,

condensed milk that the Greeks often bought. As she was a good milch goat, we

thought that they should be too. Cleo only had one kid, but as it was a female,

we decided to keep her as well. She was so frisky that we called her, “Fjolla”,

which is Danish for, “a little crazy”. She turned out to be well

named. Maria gave birth to two male kids, so I sold them to a local butcher.

To be sure that we were paid the right price per kilo for these, I had to be

there when they slaughtered them and weighed the clean amount of meat. I had

never witnessed this before and it wasn’t easy for me to see, but it had

to be done. In fact, it was a quicker, cleaner process than that which happens

at most slaughter houses, and the animals were not frightened in any way. I

didn’t take any of the meat that time round, but we have subsequently

eaten lots of meat from animals we have raised ourselves. I firmly believe that

people who like to eat meat should visit a slaughterhouse at least once, so

that they know what an animal has to go through before it appears on their plates.

I am sure we would have many more vegetarians if they did that. The following

year, Fjolla, who was then a mature goat, gave birth to a single male goat who

we named “Josif”. Unfortunately, Josif wandered into Gertie’s

stall immediately after his birth and got Gertie’s smell on him so Fjolla

would have nothing to do with him and was even butting him quite hard to push

him away. Gertie would also not suckle him (she had two of her own to feed),

so we had to hand feed Josif using a bottle with Fjolla’s milk. This was

fine except that Josif thought he was a human being, not a goat. He would follow

us everywhere. This wasn’t a big problem when we were around the house

or working on the land, but as soon as set off down the path to get to the car

to go to Town, Josif would follow. We had to take him close to where we had

tethered the other goats to graze, then wait for a while until he was busy eating,

and then try to sneak away without him following us. Several times, we had tip-toed

out of our land and thought we were OK only to suddenly hear Josif’s bleat

as he caught up with us. We then had to repeat the whole process of taking him

back to the other goats, waiting for a while, and then trying to tip toe away

again. Oh, what it is to be loved! Of course, our neighbours thought that we

were crazy and that we should just tie him up and be done with it, but his pitiful

cries at being left with the other goats as we walked away were just too heart

wrenching, and we just couldn’t bring ourselves to do it. Eventually,

like nearly all young male animals, he had to be slaughtered, but it was a difficult

one for us all.

One winter, when we were away in Holland working and friends from New Zealand

were looking after the farm, Maria managed to get her rope around a tree and

then around her neck, and then strangled herself. This happens sometimes and

it was not Mike & Lynn’s fault. However, upon our return, I determined

to make part of The Barn a proper goat shed and make a large outside area in

which they could run free. I made an ingenious system (which I had seen in France)

which trapped the goat’s heads in while they were feeding. They could

then be milked with ease and were quite happy as long as there was some hay

or bran in front of them.

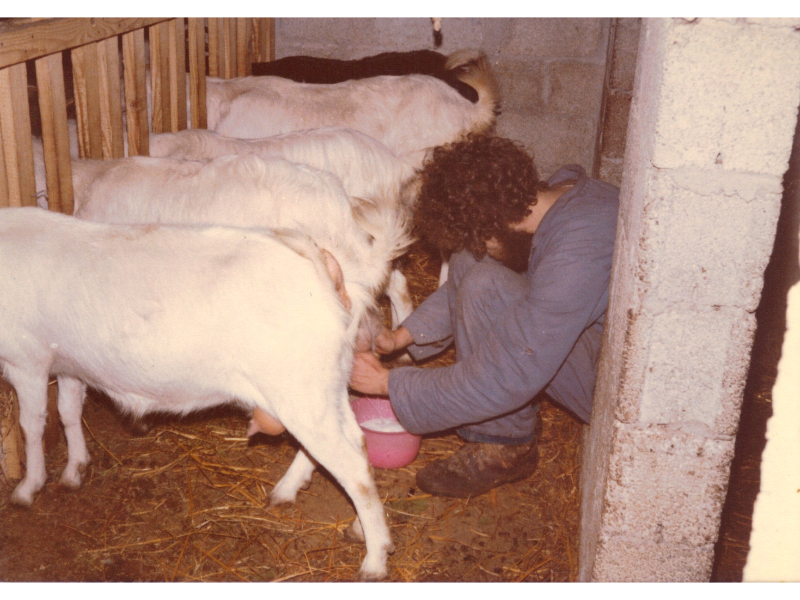

Goats eating

And me milking them

We used to leave them in there feeding for an hour which I took the milk up

to house and tied up some fresh bushes for them to browse on. Just occasionally,

when we had company and the wine started to flow, I would forget to let them

out until one if us suddenly realised, with a start, that the goats were still

“in”. When I finally went to release them, the looks I got were

withering! As they weren’t allowed outside their pen, and I no longer

wanted to have any tethered goats, I had to cut wild bushes and bring those

to them so that they would have some fresh food to browse on. In spring, summer

and autumn, this was usually a pleasant job and I would go up into the hills

every day, cut some branches of the wild scrub, and bring a bundle back over

my shoulders. One bundle was more or less enough for one day. However, in the

winter, it was no fun at all cutting bushes with water dripping off them and

rain or snow trickling down my neck. Whenever there was a fine day, I would

take Mavi up into the hills and cut as much as she could carry so that I had

enough for bad weather days. It didn’t always work and there were still

sometimes when I found myself hacking away at the bushes in the rain and wind

wondering why we ever though that goat keeping could be fun! The goats also

loved the prunings from the olive trees and as pruning was a winter time job,

I could do a couple of trees a day and keep the goats happy with lots of fresh

green. The Greeks say that the olive tree was a gift from Athena, the Goddess

of Wisdom, and was one of the finest gifts that could ever be given. Olive trees

will grow on marginal land where not much else will thrive. Cured olives are

delicious and an excellent source of food and vitamins. Olive oil is, of course,

one of the best oils in the world. However, the tree also produces food (in

the form of prunings) for goats, sheep, mules and donkeys, and olive wood is

one of the best woods for burning as it also has oil in it which makes it burn

brightly. When burnt, it leaves excellent coals on which to barbeque meat and

fish, and one of the typical “smells” of Greece is this special

barbeque aroma. Thank you, Athena! Wily old Dionysus, however, gave the Greeks

the grapevine so that they could get high and he could take advantage of the

women! But I digress. Goats have a bad name for being very destructive. It is

true that they can survive on almost anything, but they do not choose this naturally.

In nature, they are browsers and will move along just nibbling here and there,

not ever taking enough to kill a bush or shrub (their favourite food). However,

if they are confined and having nothing else to eat except what is in that confined

area, they will eat everything when they are left hungry. As usual, it is man

that creates these sorts of situations, but it is the goat that gets the blame!

A corollary can be drawn here where the poor of this world are confined (by

economic constraints) to virtual ghettoes and who end up destroying their environment

and themselves (with drugs), because they cannot get out. The well off then

give them the blame for this destruction and make being poor some kind of disgrace!

We eventually gave up the goat keeping once we had a good source of water and

could plant a commercial market garden. We still kept a couple for a while,

but you have to be there for them night and day and have to milk them on a regular

schedule otherwise their milk will start to dry up. This, plus the cheese making,

was an incredible tie, and as our girls grew older, we wanted to decide for

ourselves what we would do with our time. To make cheese doesn’t require

a lot of effort, but you have to do things all throughout the day at regular

intervals, so it also keeps you tied down. We started to understand why the

average peasant, given half a chance, would give up living on the land and go

and work in a factory for 40 hours a week AND have a few weeks holiday as well.

If you have animals and are trying to be self sufficient, you never stop! We

stopped keeping chooks (as the Aussies call them) after a while because they

started eating their own eggs! It was our fault for keeping them too confined,

but we didn’t know that at the time. Now we keep chooks again but give

them a large area and move them 4 times a year so that they always have some

greens and good scratching. We also keep them well fed and they produce eggs

all year around (much to our neighbour’s surprise and exasperation, and

theirs tend to stop laying when it gets too hot or too cold).

Barba Mitso also kept bees and offered to teach us beekeeping. I was game for

anything, and besides, I love honey! I built a wooden hive using an old one

as a template and then Mitso divided the bees in one of his hives, just before

they would naturally swarm, and put them in our hive. He often worked with the

bees without any protection, just using smoke to calm them, and never seemed

to get stung. However, when he took me to our hive to “introduce me to

the queen bee” as he put it, I was so nervous that it upset the bees and

he got stung quite a bit. “You are not for bees!” he said, and I

admitted that I didn’t think I would ever be comfortable around them.

We gave him our hive and he gave us some kilos of honey the following year although

we had done nothing to deserve them.

Us with our "mama puss" who lived to be 20

We have always kept cats. I love them and their independence. We are not sure

who the “bosses” are, but I suspect it is the cats! We also had

a couple of dogs that we inherited from people that left the island. One was

a Skiathos street dog called “Lady” and was one of the smartest

animals I have ever met. We looked after her one winter when her mistress, Eleni,

went back to Australia for a few months. The first day with us, she disappeared.

I went to town the next morning (some 10 kilometres away) and there she was,

waiting outside the garden gate of Eleni’s residence. I put her in the

car and brought her back to Zorbathes. She disappeared again and the next day

we went through the same routine of bringing her back from her home. She then

understood and stayed with us for the months that Eleni was away. Not having

telephone in those days (let alone email!), we had no exact idea when Eleni

was returning (but Lady did!). We woke up one morning and Lady was gone. That

same day, Eleni returned to find Lady sitting outside the garden gate waiting

patiently for her. How she could have known when Eleni was coming back, we never

figured out as she could not have picked up any subliminal clues from us. When

Eleni finally left to go back permanently to “Oz”, we agreed to

look after Lady, and she lived with us for her last years and was the perfect

house animal. Never a bother, but always there to guard the house and kids,

and always grateful for any attention bestowed upon her. I love dogs but find

that their demands are too much for me. They give a lot, but need a lot, and

you cannot just go off and leave them as you can with cats, as they are “bound”

to you, and I find this too claustrophobic. Our cats take our absences in their

stride, and as long as someone comes to feed them, they don’t mind at

all. Lady was one of the few dogs who was totally devoted, but never made me

feel tied down. She finally got a terrible infection in her mouth and we discussed

how to put her down with Liesbeth, Lida’s sister, who was a nurse. There

were no vets on the island at that time and Liesbeth suggested getting Lady

to eat lots of valium so that she would just drift off. We managed to get the

valium down her without problems but shortly afterwards, she disappeared. We

never found her or her body. She must have known that it was “time”

and disappeared somewhere to quietly die.

Our other experience of inheriting a dog was not so good. His name was “Podger”

and he came originally from Iran. He was not a bad dog but was very nervous

and known to bite when he felt threatened. It meant we could not keep him in

the house (he had tried to bite Mara who had simply stumbled over his tail)

and had to keep him tied up outside. I took him for a walk every morning and

evening but did not dare let him off the lead. This was no life for any of us

and we were quite relieved when he finally got too old to live comfortably and

we had him put down.

We still have cats and chickens and have tried to keep a pig one year, but it

was not a great success, and Lida has decided that we should be happy with what

we have …... so I am!

<Back to contents> <Next chapter>